ONE GLORIOUS SEASON: HOW BASEBALL INTEGRATED DECATUR, ILLINOIS

by Stephen D. Chicoine

Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Spring, 2003, Vol. 96, No. 1, pp. 80-97.

Jim Freeman never intended to become a part of history. The Decatur native only wanted a chance to play major league baseball. That was not an easy thing for an African American to accomplish in 1952. Only five other major league teams had integrated since Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson to play for his Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. One minor league team barred a black player from playing after he made one appearance and another league attempted to expel a franchise after trying to put a black player on the field. Many circuits did not commence integrating until 1953. Even with the door open, however slightly, in major league baseball, the nation had a long way to go down the path of integration. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) legal strategy was slowly working through the courts to end segregation in schools, but the Supreme Court's landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision was two years away. Rosa Parks would not make her decision to refuse to give up her seat on the bus for another three years and Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. had not yet gained national prominence.

Freeman left high school in Decatur in February 1943 to enter the United States Army. It was in the Army that he began playing baseball. Upon his return home to Decatur in 1946, Freeman played softball on a team called The Jolly Boys. He went to tryouts for the St. Louis Cardinals in 1947 at the suggestion of Decatur sportswriter Howard Millard. Advocates of integration argued, "If he is good enough for the Navy (or Army), he’s good enough for the majors.” Freeman made a good showing at the camp but Cardinals hitting instructor "Runt" Meers confided to him that the Cardinals were just not ready to sign an African- American player. Meers recommended Freeman to a friend with the Negro League Kansas Monarchs. Harold Seymour wrote in his classic America: The People's Game: "One way children of foreign birth or parentage could fit into the new culture was to take part in baseball, and early on, many of them perceived it their badge as Americans." Even that path was denied African Americans. Baseball historian Edward G. White wrote that stereotypes of African Americans suggested that they could never be fully integrated, that "In terms of melting pot theory, certain inherently 'black' characteristics could never be melted down." Arthur Mann, Branch Rickey's biographer challenged with, "How can you call it an All- American sport if you exclude black Americans?"

Jim Freeman began the 1948 baseball season with the Monarchs, playing on the traveling team. Baseball immortal Satchel Paige was the drawing card and Cool Papa Bell, a legend in his own right, was manager. Paige had learned by this time that clowning around generated bigger gate receipts. While his assortment of pitches dazzled batters, he was equally talented as a performer. Freeman remembers Paige would pitch three innings and then take off in his chauffeured Cadillac. Jackie Robinson's 1947 season in the major leagues was the beginning of the end for the Negro leagues. The Cleveland Indians signed Satchel Paige for the 1948 season while the Monarchs traveling team was in Fargo, North Dakota. The team fell apart and Jim Freeman ended up in Minneapolis, playing for Harry Crump's

Colored House of David and the Broadway Clowns. These teams also would vanish in a relatively short period of time. As several owners of Negro League franchises predicted, the end of segregation in baseball meant that fewer African Americans would earn a living from baseball due to the demise of the Negro leagues. It would be many more years before major league franchises hired African Americans as front-office personnel, coaches, and managers.

Baseball fans of all persuasions could not help but take note of the Cleveland Indians' 1948 American League pennant and World Series championship led by African Americans Larry Doby and Satchel Paige (Paige, the oldest rookie ever to play in the major leagues, finished the season with a 6-1 record, but never again pitched as well). The fact that Cleveland also set a major league attendance record that season (one that stood for thirty-two years) convincingly destroyed the argument that white fans would never support an integrated team. Yet, while the beginnings of integration in major league baseball were promising, early racial breakthroughs in major league baseball arguably had less impact on countless small towns across America. Television, after all, was only just being introduced into American homes.

Decatur, Illinois had a long tradition of baseball since the days following the Civil War. Decatur was a charter member of the Interstate League formed in 1888. The minor league Commodores, often referred to as the Commies, had been in Decatur since 1903.14 Fans Field, built in 1927, was regarded by many as one of the finest parks in the minor leagues. Baseball Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis himself dedicated the new stadium with Bill Veeck of the Chicago Cubs in attendance. Decatur was among the very first cities in organized baseball to introduce lighting for night games, doing so in 1932. A number of baseball greats, including Hall-of-Famer Carl Hubbell, played for Decatur in the early days and many others came to town to play against the Commies.

The railroads and associated heavy industry established Decatur as an important town in early twentieth-century central Illinois. African Americans, moving up from the South to find a new life, settled in Decatur. Although racial policies in the North were different in some ways from those in the South, segregation, while not legislated, remained an every day fact of life. Most restaurants in Decatur did not serve African Americans. They were only allowed to view movies at local theaters from the balconies. African Americans rarely attended baseball games at Fans Field unless Negro League teams were passing through central Illinois and there had

never been a black baseball player on the Decatur Commies.

Decatur was without a professional baseball team for the 1951 baseball season and it appeared for a time that the situation would remain the same for the 1952 season. The Mississippi-Ohio Valley League was prepared to expand to eight teams with league play to begin during the first week of May, but no one had stepped up to buy the Decatur franchise as March came to an end. The return of baseball to the town became a regular subject in the columns of Decatur Review Sports Editor Howard V. Millard.The Decatur Herald and Review published the Herald in the morning, the

Review in the evening and a combined edition on Sunday. Millard, in his thirtieth year writing for the Decatur paper, had been president of the predecessor Illinois State League and was part of a group of baseball boosters, known as Decatur Baseball, Inc. The headlines read "Decatur Is Returning to Organized Baseball" as a jubilant Millard reported on 8 April 1952. Dick King, general manager of the Gonzalez Baseball system, signed the contract "last night just before he caught the train for St. Louis." The season was about to start and there was little time to waste. King promptly ordered two sets of twenty uniforms at a cost of forty-five dollars each, although he had no players yet for his team. He managed five other baseball teams for Gonzalez Baseball System.

Arturo Gonzalez was an attorney in Del Rio, Texas, a predominantly Hispanic town on the Mexican border. Gonzalez first got into baseball in 1939 when he started up a team in his hometown of Del Rio to play in the Big State League. Baseball was Gonzalez's passion, but a sidelight. He was a sophisticated attorney, whose bilingual ability made him invaluable to American oil companies interested in the Caribbean region. He represented Houston oil companies, first in Venezuela and later in Cuba in the 1940s. Gonzalez met Joe Cambria in Cuba in the course of business and the two became close friends. Cambria was the man responsible over the years for numerous fine Cuban baseball players that became established in the major leagues, particularly for Calvin Griffith's Washington Senators. Gonzalez began to import Cuban baseball players into his various teams through Cambria in 1949. Arturo Gonzalez laughs when asked how a man in Del Rio, Texas came to own a baseball franchise in Decatur, Illinois. His initial response to Dick King was "What do I want with Decatur, Illinois? I don't even know where it is!" Gonzalez adds, however, that Dick King could be very persuasive about baseball matters and urged him to seize the opportunity.

Gonzalez and his wife immediately drove to San Antonio, where they caught a plane to St. Louis. Representatives of Decatur Baseball Inc. met the couple at St. Louis and drove them to Decatur. Gonzalez agreed to buy the franchise after seeing the town and inspecting the fine facility at Fans Field. The entire process took less than one month. As a result, the Decatur Commodores became one of eight teams in the 1952 Mississippi-Ohio Valley (MOV) League.

Gonzalez moved quickly to pull together players for the pending season. He hired his friend, Julio "YuYu" Acosta, as player-manager. Acosta, a veteran of the Cuban leagues, had pitched for Bill Veeck at Milwaukee in the American Association League in 1944 and 1945 and hit .330 in the Longhorn League in 1950.23 Gonzalez sent Acosta to Havana to sign some ballplayers, while he called the Secretary for Caribbean Affairs in the United States State Department to request the American Consulate in Havana begin preparing visas for the players.

Decatur also had close ties to St. Louis. Bill Veeck left the Cleveland Indians and took Satchel Paige with him to the St. Louis Browns. Decatur radio station WDZ carried Browns games and ads touted, "Drink a toast with smooth n' gold mellow Falstaff to the great game of baseball and the return of Dizzy Dean." Dean had had a fine career as a pitcher for the St. Louis Cardinals and was extremely popular throughout the Midwest. "The Pride of St. Louis," a Hollywood movie honoring Dean's career, would be released that summer of 1952. Dean was not only a big fan of Satchel Paige, but also a personal friend. Minnie Minoso and Satchel Paige became to the Midwest what Jackie Robinson had been to the nation. Jim Freeman would play a similar role for his hometown of Decatur. Baseball was leading integration, helping to change America.

The primary concern of Decatur fans in the spring of 1952 was how the Commodores would field a squad in time for the season. The Decatur Herald and Review of 13 April 1952 reported that the Commies would have a Cuban player /manager and noted that the "Little Cuban" had some "difficulty in speaking our language." Millard told readers on 20 April there were already eight players in camp and Julio Acosta was ready to leave Havana with ten more players as soon as visas could be arranged. The fact that Cuba was a multiracial society would have been a clue for Decatur fans that change was in the air. Days later, Acosta and his contingent flew to Miami and boarded the Gonzalez Baseball bus for Decatur. The 20 April Decatur Sunday Herald and Review featured a photo of four ballplayers, noting "In English or Spanish, Baseball Same to These Boys." The four Cubans were declared the advance guard of the 1952 Commie contingent. The Commies tryout camp opened on 22 April. Julio Acosta arrived in Decatur on 25 April with nine Cuban ballplayers, telling a Decatur sportswriter how impressed he was with the fine ballpark.

Millard prepared Decatur for a historical event when he wrote in his column on 24 April: "There are some states like Florida which has a state law preventing whites competing against Negroes but the trend is the other way and of course our sports have been largely responsible for it. For years Decatur fans have cheered Negro athletes on their own high school and college teams and have always been ready to give due credit to a Negro boy who stood out as a worthwhile opponent. ..." Millard continued: "... it is quite likely that some Negro boy will make baseball history in this city at Fans Field. It will be the first time that a Negro player has ever worn a

Commie baseball suit. ..." He reported the statement by General Manager Dick King at the previous night's baseball meeting that there would likely be "... one and possibly two Negroes on the club."

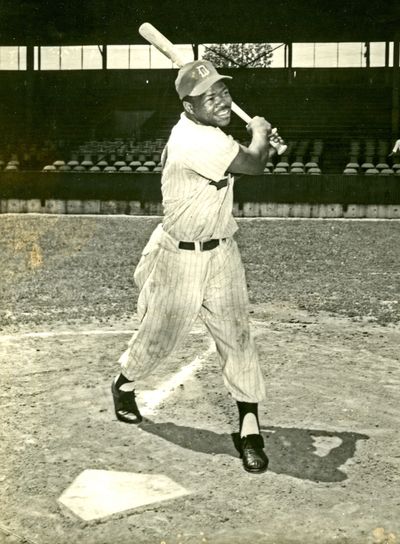

One of these was Jim Freeman. The Decatur native, who had been playing baseball in Minneapolis, returned home in the off-season. The owner of the Colored House of David died that winter and the team fell apart. The Decatur Commodores was the opportunity for which Jim Freeman had been waiting and he took it. The Decatur Herald of 29 April referred to Freeman as, "Among the better prospects." The article also mentioned black Cuban Carlos "Charlie" Paula as a likely starter in the outfield. Dick King remembers Paula as a big, strapping ballplayer (he was six feet four inches tall) with a great arm who could run like a greyhound.

Bold lettering on a full-page newspaper ad that weekend proclaimed "New Manager, New Team, New Faces, New Spirit, New Club" and read: "the Commies made up of younger players, many from the island of Cuba will give the local fans ... an interesting brand of ball." Box seats were $1.50 for the opener and general admission was $1.00 with $0.40 for children under twelve.

Opening day, Sunday, 4 May, Decatur versus Hannibal. The sports

section of the Decatur Sunday Herald & Review featured the Commodore

team photo. Cubans Pete Naranjo and Carlos Paula, along with Decatur

native Jim Freeman, shared the distinction of being the first blacks ever to

appear on a professional baseball roster in Decatur. Arturo Gonzalez and

his wife flew to Decatur on the Gonzalez Baseball plane to attend the game31

and the Decatur Review featured a photo of the owner and his lovely wife in

their box seat on the third base line.32 Gonzalez recalls as to prejudice in

Decatur, "I didn't notice any difference at all and I didn't expect any."

Four thousand fans saw the Commies knock the Hannibal pitcher out of the game in the first inning and go on to defeat Hannibal by a score of 8-5. Jim Freeman, "the Decatur Negro third-baseman" led the Commies, going three-for-three at the plate. Julio Acosta drew a few boos when he came to the plate in the bottom of the eighth, still hitless. He singled to score a run, then stole second, advanced to third and scored.

Hannibal won Monday's game by a score of 5-3. Julio Acosta started game three against Hannibal. The Stags shelled the Commies Manager and won 15-4, suggesting that Acosta, who had once been a solid AAA pitcher, had lost his touch. One of the few bright spots for the Commies was centerfielder Charlie Paula, who hit a triple and a booming three-run homer. The Commies added some talent. Veteran Catcher Andy Smith of Iola, Illinois joined the Commodores. Smith had had a promising major league career - slated to be the backup catcher for the Cleveland Indians - before he headed off to the Second World War. He distinguished himself in the Pacific Theater as a member of an elite reconnaissance unit and returned after the war with shrapnel in his arm and legs. The velocity of his throw was never again the same, but his accuracy remained uncanny. An opposing ballplayer told Jim Freeman, "Nobody throws as soft as Andy Smith and throws out as many base runners."

The Danville Dans came to Decatur on Sunday for the Commodores first doubleheader of the 1952 season. They were what Millard referred to as " ... just about an all-Boston Braves group of athletes," as the team's major league owners kept the Dans well supplied with talent. Player /manager Virl Minnis led the rough-and-tumble bunch, which reminded some of an earlier era of the game. The Commies swept both games. Jim Freeman doubled and hit his first home run of the season. The three-hundred sixty-foot shot gave Millard cause to write: "It was a lusty clout off the bat of Jim Freeman, the Negro boy with the big smile." Charlie Paula, "the big outfielder," drove in four runs with two singles and Pete Naranjo got the win. Paris edged Decatur 3-2 the following night, despite a Charlie Paula

home run.

The Commies trounced Vincennes 14-7 on 23 May and moved into a tie for first place with Danville behind "Decatur boy Jim Freeman, who put the finishing touches on" with a grand slam. Freeman, Paula, and Naranjo anchored a solid Decatur team that delighted its fans. Decatur defeated Hannibal 9-6 and 10-1 on 30 May with Charlie Paula going six-for-eight in the doubleheader. Jim Freeman, "Decatur's own outfielder," did his part also, hitting a home run, a double, and two singles and came up with a sensational shoestring catch of a line drive.

There were some problems, racial and otherwise, however infrequently. Freeman recalls racial slurs and "all kinds of trouble" in Mattoon. Hannibal fans, in contrast, were never rude or insulting to him - they would call out to him jokingly, perhaps to tell him that there was a telephone call for him as he approached the plate to hit. But Missouri was still enforcing segregation in 1952. Freeman and his fellow black teammates, unable to stay at the local hotel with their white teammates, had to spend the night in Hannibal at private homes. Then there was an incident at Danville in which Freeman pulled a couple of guys off of a teammate. The opposing players warned Freeman "We'll get you." The Decatur Chief of Police sent a couple of officers to accompany the team and protect Freeman on the next road game at Danville.

Millard's 1 June "Bait for Bugs" column addressed the integration of organized baseball in Decatur, writing, "No one can deny that there are several colorful players on the local roster, players who may go far in the profession if that is what they desire most. Then the Negro population of the city is pleased that one or more of their boys have been given a chance to compete with others on even terms for a place on the team.” Charlie Paula helped emphasize that point, blasting his fourth home run on 1 June against Mount Vernon. Decatur was red-hot, one game behind first-place Danville. When Decatur beat Danville 5-4 on 6 June, the Commies moved

into a tie for first place. Decatur had a winner on its hands and the success

on the field helped convince skeptics to accept the social change introduced

by the Gonzalez Baseball System. The 8 June Decatur Sunday Herald and

Review featured a large montage of Freeman, Paula, and Naranjo under the

heading "First Negroes Ever to Play Ball with Commies." Charlie Paula was

leading the league with a blistering .434 batting average.48 As the major

league's All-Star break approached at the beginning of July, Dick King

attempted to get an exhibition game for his red-hot Commies with the St.

Louis Cardinals, but was unsuccessful. Jim Freeman would have loved the

opportunity.

The biggest event in Decatur on the eve of the Fourth of July was the near-escape of Okey, the Fairview Park bear who scaled the eleven-foot fence that was supposed to contain him. But attention soon turned to the big holiday doubleheader against Canton. Paid attendance for the Fourth of July at Fans Field was 4,350. Pete Naranjo, in an amazing feat, rarely seen any longer in baseball, pitched two complete games for the Commies and Harvey Noland did the same for Canton. Decatur lost 2-1 in the first game in which Charlie Paula was robbed of an extra base hit on a sensational over-the-shoulder catch deep into right center. The Commies won the second 3-0.

While the baseball season proceeded into summer, the 1952 presidential race shaped up as a choice between Republican Dwight Eisenhower and Democrat Adlai Stevenson. The war against Communist aggression in Korea was well underway and American casualties were mounting. The Decatur paper regularly published mention of local boys serving in Korea. "Retreat, Hell," a movie of the Marines' ordeal at Chosin Reservoir, was playing at Decatur's Lincoln Theater. The double-threat of the Soviet Union and Communist China threatened democracy and Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin was at the peak of his power, witch-hunting throughout the

nation for Communist sympathizers. While the Republican National Convention applauded McCarthy for his call for action in the fight against "disloyalty and treason," the Democratic National Convention debated a platform to include a Federal agency to investigate racial discrimination. There were more immediate dangers. The dreaded disease, polio, peaked in the United States that year with over twenty thousand afflicted. There were over two thousand reported cases in Illinois in 1952 and central Illinois was one of the hot spots.

The Decatur Commodores finished the first half of MOV league play in third place with Danville in first place and Paris in second place. The Commies went into a slide as second half play began. Decatur led Paris 4-1 going into the ninth inning on 10 July. Paris managed to tie the score at 4-4 and send the game into extra innings. Pete Naranjo had ten strikeouts going into the thirteenth inning and lost the game on an inside-the-park home run. Paris won again the next night, beating the

Commies 5-3, and then swept the series with a 9-3 win. Decatur lost to Danville 8-5, despite Charlie Paula's two triples and again the following night to establish a five game losing streak.

The Commies refused to let their spirits fall and returned to their winning ways with gutsy play. Pete Naranjo won his tenth game in an 8-3 victory over Canton on 31 July58 Charlie Paula hit a line drive to center and scored all the way around the bases. Decatur split a doubleheader with Hannibal the next day with Jim Freeman stealing home for the winning run in the first game. Decatur's Cuban infield shone on defense. Veteran Julio Acosta anchored first base. Orlando Moreno was at second. Gus Chenard, a seventeen-year old phenomenon from Havana, played shortstop like a veteran and thrilled the fans with his outstanding defensive play and his rifle arm. Juan Medina, a twenty-year-old who Dick King claimed had "one of the finest throwing arms in baseball," came up in early June and became a standout third baseman. Twenty-three year old pitcher Guillermo "Gil" Grajeda joined the Commies from Sweetwater in early August and became best friends with Medina. Medina and the other Cuban players, who spoke only broken English, relied on Mexican ballplayers like Grajeda to order dinner for them.

By September, Decatur remained in third place, eight-and-a-half games behind league-leading Paris and six-and-a-half behind second place Danville. Pitcher Pete Naranjo, playing right field for the injured Charlie Paula, led the Commies to victory over Hannibal on 31 August with two doubles and a triple in three times at bat and three runs-batted-in. The Commies went into the final series of the season against Mattoon needing only one win in three games to clinch third place. Pete Naranjo opened for the Commies, allowing only a walk in three innings. Gil Grajeda followed

and Paul Begovac finished the game for Decatur. The trio of hurlers did not allow a single Mattoon base runner past second base. The Commies hit the Mattoon pitchers hard and came away with a 9-0 victory and a third place finish. Millard noted that even Lucille and her trick horse Daisy, who performed for the fans, outshone the Mattoon club that night. That did not detract from the Decatur team’s first finish in the top half of the league in a decade. Mattoon won the next game by a score of 5-2. The series and the season closed with the Commies taking a 7-6 eleventh inning win. Decatur manager Julian Acosta used six pitchers, only one who was a pitcher in the team rotation. Even business manager "Tiny" Chapman got in the game. The four hundred pound ex-football player caught the first inning and singled in his lone at-bat. Millard referred to Chapman's hit as a "Mountain Side" liner and claimed a record had been set for the heaviest ever Decatur ballplayer. The real highlight of the game was the presentation of the most popular player award. Mayor Robert Willis gave catcher Andy Smith a Bulova Watch from Carson's Jewelry Store on behalf of the collective vote of the hometown fans.

Third-place Decatur began the Shaughnessy playoffs on Friday, 5 September at Paris, facing the second-place finisher in a best-of-five series. Only four players had been with the Commies since opening day, Charlie Paula, Jim Freeman, Pete Naranjo, and Gus Chenard. The Decatur-Paris winner was to playoff against the winner of the series between pennant winner Danville and fourth-place Hannibal. Paris had won the previous season's pennant and Danville the Shaughnessy playoffs and the two were favored to square off again for the championship series.

Paris boasted a solid lineup of hitters, foremost of whom was Clinton "Butch" McCord. The Negro League veteran finished the 1952 season with a .395 batting average and his second straight MOV hitting title. McCord had the power to go with the average, blasting fifteen home runs during the season. McCord's hitting prowess caused Millard to write in his column, "Why is Clint McCord still playing in the MOV after a great season in 1951 is a question many baseball fans have been wondering." Nor could opponents pitch around McCord. Lakers teammates Jim Zapp, also a Negro league veteran, finished the season with a .330 average, twenty home runs and a record-setting 136 runs-batted-in.

The Paris Lakers opened the playoff series with fifteen-game winner Jim Paolo. Paolo held Decatur for eight innings, while the Lakers put on a hitting exhibition. Jim Zapp hit his twenty-first home run of the season and Gene Brand his thirteenth. The score was a lopsided 11-2 going into the bottom of the ninth. The Commies gave it all they had in the ninth inning with Phil Rizzo and Charley Paula blasting home runs. But four runs were not enough and Paris came out on top, 11-6. Decatur faced Paris ace Neil Maxa in game two. Maxa boasted twenty-one wins on the season. The Commies went with Paul Begovac on the mound. Decatur leadoff hitter Phil Rizzo set the tone, starting the game with a home run. Paris tied the game in the fourth when Butch McCord drove in a run. Decatur took charge in the sixth. Jim Freeman smashed a bases-loaded double to right center to score three runs and Rocky Carlini followed with a two run homer over the left field fence. Paris had big

innings in the eighth and ninth, but it was not enough. Begovac went all the

way for Decatur, allowing just seven hits and the Commies evened the playoffs at one-to-one.

The series shifted to Decatur's Fans Field for game three on Sunday afternoon with a crowd of 1,285 in attendance. Commie pitcher Pete Naranjo pitched three good innings before being knocked out in the fourth as Butch McCord continued to plague Decatur pitchers. Paris won 4-2 to put the Commies in a do-or-die situation.

Review Sports Editor Howard Millard noted that the entire season rested "on the good right arm of little Gil Grajeda" for game four. Jim Paolo started the game for Paris, but the Commies jumped on Paolo for two runs in the second inning and added two more in the third at which point he was relieved. The contest was heated and the umpire threw the Laker catcher out of the game in the third inning and a Laker relief pitcher in the fifth inning. The Commies had a commanding 10-1 lead after five innings. Paris scored two runs in the eighth when McCord singled and Chadwick drove a shot way over the left field fence. The Lakers had another rally

beginning in the ninth with a runner in scoring position. Jim Freeman put an end to that with a spectacular one-handed catch of a long drive by Quincy Smith, the Lakers leadoff hitter. Grajeda fanned Laker Jim Turner to end the game and the Commies tied the series at two games each. Grajeda pitched nine full innings for the Commies, giving up only nine hits while fanning eleven and walking only two. Butch McCord went three-for-four with a triple and Doyle Chadwick hit a homer for the losers.

The Decatur Review announced "Final Battle of Paris Set Here Tonight” Millard wrote of the ejections of the two Paris players in the previous game: "The fans liked it all very much and should be back tonight not only for the game but any side shows that may be provided." The game was hard fought from the start. Paris opened the game by scoring and Decatur responded with four runs in its half of the first inning. Decatur led Paris by a slim 7-6 margin after six innings. Commie reliever Larry Higgins came in and allowed only one hit in the last three innings to clinch the game and the series for the ecstatic Decatur fans. A stunned Paris went home,

their season over.

The local editorial staff for the Decatur Herald deserved as much acclaim from the hometown fans as the Decatur Commodores themselves. An 11 September editorial boldly attacked Senator Joseph McCarthy's "irresponsible approach . . . under the guise of patriotism." Meanwhile, the polio epidemic continued to ravage Illinois and the nation. Casualties continued to mount in the bloody fighting in Korea. Baseball remained a welcome distraction that fall of 1952.

The championship playoff was an improbable match-up between Decatur and Hannibal after the Stags shocked Danville three-games-to-one in their series. While perhaps not as formidable as Paris, Hannibal featured the power hitting of big first baseman Sam Wiggins and a solid pitching staff. Former Commie Nick Starasta provided solid catching for the Stags. Hannibal, not expecting to be in the playoffs, had leased out their ballpark to an outdoor show. Consequently, the entire series was played in Decatur at Fans Field.

The opening game of the championship playoff between Decatur and Hannibal was a thriller. Neil Maxa, star pitcher for Paris, was allowed to sign and play for Hannibal in the series. He held the Commies to only six hits. Pete Naranjo was equally tough on the mound, giving up only six singles and not allowing a single runner past second base. He coolly worked himself out of several jams with base runners on first and second. Naranjo also hit a double in the sixth inning and scored the game's only run, as well as adding another double in the ninth. Decatur won 1-0 and Naranjo

earned his fifteenth victory of the season. Millard wrote that Naranjo had the best control at his age of any lefty who had ever pitched for the Commies. The praise was particularly noteworthy, as Millard had seen thirty years of baseball in Decatur, including Hall-of-Fame pitcher Carl Hubbell. He suggested that he was not alone in considering Naranjo as the best Decatur prospect for the major leagues.

Game two was another thriller. Decatur led early on 1-0. Hubert Brooks kept Hannibal scoreless for six innings until being knocked out in the seventh. Hannibal led 4-lgoing into the bottom of the ninth inning. Hannibal hurler Armando Diaz, a nineteen game winner with an earned run average of less than a run per game, seemed in complete control. When Gus Chenard grounded out for the first out, some fans began to head for the parking lot. That was when Bob Leonhard turned the course of the game, ripping a sharp single. Charley Paula also connected for a single to advance Leonhard and some of the departing fans in the aisles took a seat. Stag manager Nick Starasta ordered Diaz to walk Julio Acosta to load the bases and set up a double play. Andy Smith drove in Leonhard with a ground ball that forced out Acosta at second base. Jim Freeman stepped up to the plate with two outs and the Commodores behind by a score of 4-2. Millard recalled that Freeman "could not have looked worse on one swing.” The veteran ballplayer dug in and waited for his pitch. He brought the crowd to its feet with a double off the center field fence that drove home two runs to tie the game and sent it to extra innings. Hannibal was unable to get anything going in its half of the tenth inning. The Commies carried the emotional edge from the seemingly improbable salvation in the big ninth inning. Decatur shortstop Phil Rizzo hit a high hopper off the third baseman's glove that was scored a hit. A desperation throw, recognizing Rizzo as the winning run, went over the first baseman's head into right field. The speedy Rizzo went all the way around the bases and scored to the delight of fans - only to be sent back to third

base on a ground rule. A screaming line drive by Bob Leonhard right at the third baseman almost doubled off Rizzo but for his quickness. Hannibal again elected to intentionally walk the veteran Acosta and pitch to Andy Smith with two outs and the bases loaded. Smith coolly sent a drive into center field to score Rizzo and win the game for Decatur. There was pandemonium at Fans Field.

In the third game, Cuban southpaw Amanico Ferro, who had dazzled Danville in the preliminary playoffs, started for Hannibal. Ferro threw a two-hitter against Decatur, setting thirteen Commies down swinging. More than two thousand fans showed up at Fans Field in anticipation of a celebration that was not to be.

Sunday, 14 September was the final day of the season. Game four began at 2:30 in the afternoon. It was agreed that if Hannibal won and a fifth game was necessary that the game would be played that evening at 7:30. Republican vice presidential candidate Richard Nixon was interviewed on "Meet the Press" on WMAQ radio that morning. One can imagine that Decatur was not focused for the moment on the ensuing election.

The fourth game of the 1952 MOV Shaughnessy Playoffs pitted Decatur's Pete Naranjo against Hannibal's Boots Budde. Howard Millard noted with concern that the former Millikin University standout, "can be mighty mighty tough out there on the rubber." The game was a masterful pitching duel for nine full innings with neither side able to put a run across the plate. Naranjo set down the Stags in order in the second, fourth, fifth, sixth, eighth and ninth innings. Hannibal had only two hits against Naranjo. Budde was also tough. Decatur threatened only in the third inning when Jim Freeman led off with a walk and advanced to second on a Carlini single. But Budde settled down and retired the next three batters. Jim Freeman led off the top half of the tenth inning for Decatur. He ripped a sharp single to center that got away. Freeman ended up at third base with no outs and Decatur fans were on their feet.

Decatur had won only one playoff championship in its entire history, that being in 1938. Rocky Carlini grounded to the third baseman, but was distracted enough trying to hold Freeman, that he overthrew to first base. The Decatur Review of the following day featured a photo of Freeman scoring. Gus Chenard beat out a hit to shortstop with two outs, scoring Carlini. Bob Leonhard singled to right to advance Chenard and "Charlie Paula got the last hit of 1952 season" to score Chenard.

Pete Naranjo set down the Stags one-two-three in their half of the inning and Decatur won the championship series. Bob Fallstrom of the Decatur Herald wrote, "the 1,468 fans whooped it up in no small manner."

The Decatur City Council met on Monday and passed a resolution to officially designate Monday, 15 September 1952 as Decatur Commies Day. The City Council, noting the importance of the season in more ways than one, noted: 'Whereas a timely hit by a Decatur boy named Jim Freeman played no small part in this splendid tenth inning triumph, therefore, Be it resolved ... that all citizens are charged particularly with offering congratulations and felicitaciones to these men as occasion arises, and especially to Decatur resident Jim Freeman.'

The Decatur Review included a feature that same day on a one hundred year old man in East St. Louis. Henry Fuller, born a slave in South Carolina in 1852, reminisced about seeing Mr. Lincoln as a young boy and insisted that Lincoln was the first President of the United States as he was the first to begin to bring the nation together. Nearly one hundred years later, the United States was finally getting on with the job. The 1952 Decatur Commies played their small role in the larger game.

The Gonzalez Baseball System continued to own and operate the Decatur Commodore baseball franchise through the 1954 season. The Commodores opened the 1953 season with eleven members from the 1952 squad, including Jim Freeman, Andy Smith, Charlie Paula and Pete Naranjo.

The Commies won the MOV League pennant that year and repeated in 1954. Then Gonzalez Baseball System let the Decatur franchise go. The Commodores never again had the success, which they experienced under the Gonzalez Baseball System, winning the league only once in the next twenty years and often residing in the second division of the league.

The last Decatur Commodores team played in 1974. Decatur's Fans Field no longer exists. It broke Jim Freeman's heart to see the classic stadium torn down. Arturo Gonzalez was quite disappointed to hear of its demise. As John Clifford wrote in Mostly Minor Leaguers, his history of the Decatur Commodores, "To this day the decision to dismantle the grandstand prompts debate."

Jim Freeman still resides with his wife in Decatur on Rogers Street, where he has lived for many years. He is content with his life and speaks with enjoyment of his days in organized baseball. He had three good years with Decatur, but never made it to the major leagues. By the time that the St. Louis Cardinals finally integrated in 1954, Freeman was thirty years old, old enough to move on beyond the Commies and find a new career beyond baseball. Men like Freeman, Butch McCord, Quincy Smith, and others were talented African American baseball players perhaps just a few years ahead of their time. Then again, they accomplished so much as it was. Baseball historian Edward G. White wrote: "by 1953, when it appeared that baseball

was very much the same enterprise it had been in 1923, or even, in some respects, 1903, it was in fact already on its way to becoming a radically different enterprise."

Jim Freeman kept in touch with his good friend Andy Smith over the years. He traveled to attend the memorial service last year upon Smith's passing. Andy Smith's remains are interred in Arlington National Cemetery. Charlie Paula became Carlos Paula, the first ever African American to play for the Washington Senators. His .299 batting average was highest among American League rookies in 1955, but his stay in the big leagues was brief. His fielding was less impressive than his hitting, according to one long-time Senators fan. Further, the Senators began

accumulating power hitters. Paula bounced around afterwards and passed

away in 1985. Pete Naranjo, to the surprise of Howard Millard and others,

never made it into the major leagues. He played ball somewhere in Mexico

for a time and has not been heard from for years.

Dick King remains active as ever in baseball as the head of the All- American Association of Baseball Clubs. Arturo Gonzalez is alive and well at the age of ninety-four. He still goes to his law office in Del Rio every day and recently celebrated his sixty-seventh year as an attorney.

The integration of America was a long slow process and involved many heroes, some of them whose names are in danger of being forgotten. Each region and each town within that region was another struggle within itself. Baseball was very much a part of America's fabric of society in those days, arguably more so than today. Men like Arturo Gonzalez and Dick King helped to change Decatur, the Midwest, and America, as did Jim Freeman, Charlie Paula, and Pete Naranjo.

This article, complete with photos and footnotes, is accessible on JSTOR.

OBITUARY FOR JIM FREEMAN

DECATUR - James Andrew Freeman, 81, departed this life on Wednesday, September 6, 2006 in Decatur Memorial Hospital. James was born February 12, 1925, son of John Freeman Sr. and Naomi Mae Taylor, in Decatur. He was a member of the Church of the Living God, CWFF.

He graduated from Stephen Decatur High School, where he participated in baseball. Later he attended a St. Louis Cardinal's try-out camp, where he out performed every out-fielder in the camp. He later had the opportunity to join a new team called the Decatur Commies MOV League; averaging 90 RBI's per year.

Decatur native Jim Freeman, along with other shared the distinction of being the first blacks ever to appear on a professional baseball roster in Decatur. He also played with the Kansas City Monarchs. His teammates included Leroy Satchel Paige and James "Cool Papa" Bell, both Hall of Fame inductees. Later, he played for the Champaign Eagles E1 League. After a few seasons, he helped form a team in the Decatur City League known as the Jolly Boys. He loved baseball and had the backing and support from various ones throughout the City of Decatur.

He was a Veteran of the U.S. Army. He was the first black Supervisor with the City of Decatur Water Department, retiring after 34 years of service. He united in Holy Matrimony to Lillian M. Howard on February 14, 1951. He leaves not to mourn but to cherish fond memories, his loving devoted wife of 55 years, Lillian; sisters, Ruth E. Slater, Ethel Hatten, Mattie (Willie) Tucker-Green and sister in law, Katherine Freeman all of Decatur; brother, Olive (Beverly) Freeman of Decatur, and a host of nieces, nephews and other relatives and friends. He was preceded in death by his parents, two sisters and two brothers. We, the family, will miss our Advisor, Counselor, Administrator, Chef and Our Hero! But, we'll see you in the morning. Celebration of Life Services will be 11:00 AM Monday, September 11, 2006 at the Church of the Living God, CWFF with Pastor Carter officiating.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.