LITHUANIA: THE NATION THAT WOULD BE FREE

written by Stephen Chicoine and Brent Ashabranner

photos by Stephen Chicoine

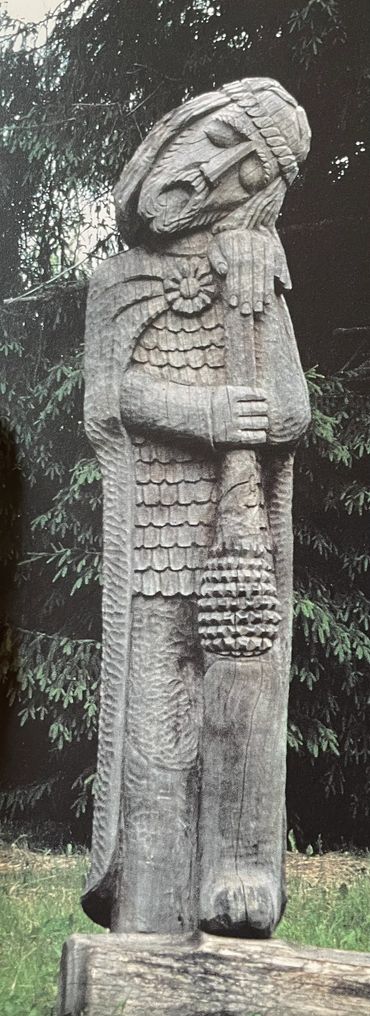

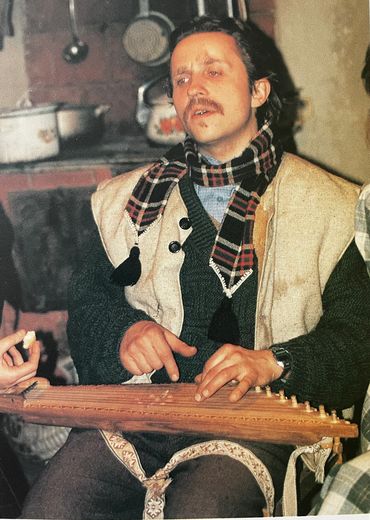

This book for young readers, recipient of an award from the Washington Book Writers, relates the personal experiences of author Stephen Chicoine on his travels through Lithuania in the year after its independence from the former Soviet Union in 1992.

ADDITIONAL PHOTOS OF LITHUANIA BY STEVE CHICOINE

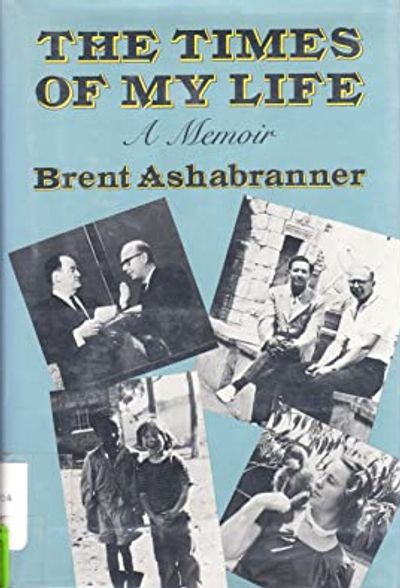

BRENT ASHABRANNER - MY WRITING MENTOR

Lithuania was my first book

Steve Chicoine on Brent Ashabranner (and Paul Conklin)

I first met Brent Ashabranner through Paul Conklin. Paul was the first photographer for the Peace Corps. Brent was a friend of Sargent Shriver, who became a Deputy Director of the Peace Corps. Brent collaborated in writing with Russell Davis for a time and later collaborated even more extensively with Paul Conklin on a series of books for young readers. Both partnerships conveyed the rich diversity of cultures in the world and presented

I met Paul in Xinjiang Province, far western China, in 1986. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) had just re-opened the region to tourism. It had been closed to the West since the conquest of the land by the People’s Liberation Army in 1949. This is the land of the Turkic ethnic Uyghur People. They lived in the isolated oases across the formidable Taklamakan Desert. The trade route known as the Silk Road traversed the region. Buddhist missionaries from India brought Buddhism to China along this route in the early 1st century. Marco Polo traveled the road from Venice to Imperial China in the 13th century. The region featured vast Buddhist ruins, immense cave complexes with intact murals and statues, as well as magnificent Islamic mosques and minarets. I extensively studied the history and culture of the region for months prior to my trip.

I spent a month alongside Paul, asking questions about photography. I also closely observed his style in unobtrusively merging into a crowd to gain position and capture priceless images. I had self-taught myself the technical aspects of the lens. I even had a reasonably good sense of composition of images. I did not yet have the confidence to shoot portraits, even with a zoom lens. The key was to get close and capture eyes and facial expressions, emotions. I learned that and much more from Paul on the long bus and train rides. My photos from that excursion were strikingly better than my previous tourist snapshots. The experience forever altered my photography and launched a lifetime hobby.

Paul was taking photos for a book project. He had been the official photographer for the Peace Corps. He collaborated with his friend Brent Ashabranner, who had been a Deputy Director of the Peace Corps. After we returned to the States, Paul approached me. He knew little about the history and culture of Xinjiang, nor did Brent. Much of what I knew came from library research in very obscure volumes. This was pre-internet. I agreed and, in this way, I came to know Brent Ashabranner. Of course, I was thrilled. Ashabranner had a long list of books to his credit. I recognized the opening. I was hoping that Brent and Paul would offer me a co-authorship. I had been writing since I was six years old and was seeking a break to launch a side career in writing through Brent. In the end, I was disappointed. I was not a co-author. They did dedicate the book to me. Land of Yesterday, Land of Tomorrow: Discovering Chinese Central Asia (Dutton Books for Young Readers, 1992).

I traveled in Tibet in the following year, 1987. As with Xinjiang, P.R.C., I spent a year, in advance of my journey, researching obscure historical and cultural sources in university libraries. I was witness for a month to mass Tibetan demonstrations crying out for an end to methodical cultural genocide under the Chinese occupation. The ironically named People’s Liberation Army brutally suppressed the demonstrations. I was traveling with a Tibetan scholar. That allowed me to meet and talk with Tibetans about the night-time home invasions and the disappearance of their young men.

I proposed a book on early explorations in Tibet to National Geographic Magazine. They repeatedly expressed great interest, including Gilbert Grosvenor himself. Nothing ever came of that, despite repeated assurances of considerable interest. They published that through another author. I became very disenchanted with the publishing industry after not only being misled, but also seeing my idea used in a very similar book. That was the second time that happened to me. Brent continued to encourage me to stay the course.

I supported and worked with the International Campaign for Tibet ever since returning from Tibet in 1987. With Brent’s encouragement, I proposed a book on the Tibetan refugee situation to Lerner Publishing in Minneapolis (I was still living in Houston at the time). Lerner insisted that I first fill a void they had in a refugee series. In late 1995 and into 1996, I interviewed and photographed a Liberian refugee family in Houston. The result was A Liberian Family: Journey Between Two Worlds (1997). That led to A Tibetan Family: Journey Between Two Worlds (1998). These were very much aligned with the works of Brent and Paul.

I maintained contact with Brent and Paul following my work with them on their Land of Yesterday, Land of Tomorrow: Discovering Chinese Central Asia. Our relationships evolved and deepened. We became good friends. I traveled to see them (Brent was in Williamsburg, Virginia and Paul was in Washington, D.C.) and they traveled to see me in Houston over the years.

I closely followed developments in the Soviet Union under Gorbachev, watching the news, devouring the daily editions of the New York Times. I traveled to Gorbachev’s Soviet Union in July-August 1989 to see what was happening. I roamed the country solo for a month, observing, photographing and meeting those who could speak English. I made a point of going to Tbilisi, Georgia to visit the site of the April 9, 1989 attack by Soviet internal security forces on pro-independence forces. The Soviets killed 21 and injured hundreds. The Berlin Wall fell on November 9, 1989. I was unable to sell any of my proposed writings with photographs on the situation in the Soviet Union.

Saddam Hussein’s Iraq invaded Kuwait on August 2, 1990. The U.S.-led coalition built up forces until January 17, 1991 at which time Operation Desert Storm commenced. I was following the situation in the Soviet Union and, in particular, in Lithuania daily through the New York Times. I was convinced that too much attention was being paid to the Gulf and not to Eastern Europe. Tensions were soaring between Lithuania and the Soviet Union. I wrote letters to the federal government and to editors of major publications. As I feared, on January 13, 1991, Soviet troops attacked Lithuanian protestors attempting to prevent a Soviet takeover of the television tower in Vilnius, the Lithuanian capital. Fourteen Lithuanians died. Hundreds were wounded.

I was traveling to and from Russia on oil business from 1991 onward. In June 1992, I made my way to Lithuania to spend a week there. The anti-tank barricades were still up. Children’s anti-Soviet art was posted throughout the city of Vilnius. The graves of those killed by the Soviet troops were still fresh dirt. I met and spoke with many Lithuanians in Vilnius and beyond.

I spoke with Brent Ashabranner about my experiences in Lithuania. I shared some of my conversations, observations and photographic images. Brent encouraged me. He pitched his editor at Dutton Books for Young Readers. That led to a proposal and a contract. The editor agreed to publish my book on the condition that Brent co-author with me. Of course, I accepted. I learned a great deal about writing for young readers from Brent. The experience was priceless. Dutton Books for Young Readers published Lithuania: The Nation That Would Be Free in 1995.

Brent arranged for the publisher to send me the proof of the book cover, which featured not only my name with Brent’s but also one of my photos. I was awestruck. I immediately called Brent. I remember him chuckling over my delight. He was so happy.

Brent arranged a book signing at a Washington, D.C. bookstore, The Cheshire Cat. Jewell Stoddard and three other women founded the Cheshire Cat in 1977 (they closed in 1999). The store was jammed with people. The entire experience was chaotic verging on surreal. It was a literary extravaganza. Such was the reputation of Brent Ashabranner. I still have my name tag with the Cheshire Cat logo.

I continued to share my ideas and writings with Brent. He was always supportive. Brent was not someone to sugarcoat his words. If he was not satisfied with my writing, he told me so. I sincerely appreciated that and worked earnestly to respond each time with better revisions. Brent praised my ability to find interesting subjects. He enjoyed my books and my articles. I still remember Brent’s praise after reading my piece on “The Great Gallia,” the story of the baseball career of a South Texas schoolboy, discovered in 1910, who rose to prominence in major league baseball for a brief career. Brent referred to that piece at the time (2001) as the best I had ever written. I still glow when I recall that.

Brent Ashabranner and Paul Conklin wrote and published many meaningful books on social justice for young readers. They understood well the importance of literature as a means of facilitating moral education. Paul used my home in Houston as a base for bird watching and photography in South Texas. At one point, Brent and Paul were working on one of several books, which they published, on the U.S. border situation, immigration and the lives of those seeking a new life in the United States.

I was volunteering in those days with Casa Juan Diego, the Houston outpost of the Catholic Worker Movement effort (followers of Dorothy Day), established by Mark and Louise Zwick. Paul knew that I was active in social justice. At the request of the International Campaign for Tibet in 1995, I organized the three-day visit of the Dalai Lama to Houston. Among the many events, which I arranged, was a breakfast with the Dalai Lama and my friends and acquaintances, who worked in social justice. Those included a Houston police officer working with gang members, inner-city teachers, social workers, volunteer tutors and mentors. Among those were the Zwicks from Casa Juan Diego.

Paul Conklin asked me to introduce him to the Zwicks for his latest collaboration with Brent Ashabranner. I approached Louise Zwick. Many Texans did not support the Zwick’s selfless sharing of compassion and resources with those, who had crossed the border. Louise was a tough woman. She had to be. She was skeptical of my request until I invoked the name “Brent Ashabranner.” Her eyes lit up. Louise was a children and young adult librarian in her prior life. She was thrilled and told me that Paul would be welcome to visit Casa Juan Diego and photograph her people. That moment said so much about Brent Ashabranner and the respect, which he earned from librarians of that era.

Brent loved his martinis. As with many who worked overseas, a drink or two in the afternoon became part of his ritual. I once reminded Brent that I had never in my life had a martini until I met him. Brent chuckled and commented that perhaps that was the most important thing he taught me. He said that with a wide grin, proud to have shared with me all that he knew about writing and the publishing world.

Brent was passing on to me what he knew, just as his writing mentor had done for him. Thomas H. Uzzell studied writing at the Columbia University School of Journalism in the 1910s under Professor Walter B. Pitkin. In 1923, Uzzell and Pitkin co-authored a book titled Narrative Technique: A Practical Course in Literary Psychology. Uzzell was a fiction editor at Collier’s Magazine for a time. He taught writing seminars at New York University and published several books on the craft of writing. While at NYU in 1938, Uzzell was retained by Alcoholics Anonymous to edit a manuscript which became the “Big Book.” By the 1950s, Thomas Uzzell was a professor of English at Oklahoma A & M University (now Oklahoma State University), Brent Ashabranner’s alma mater. Brent told me that Uzzell “was a great writer. He practically adopted me. I was his assistant.”

In 1955, the Truman administration’s Point Four Program reached out to Oklahoma A&M for assistance in opening an agricultural college in Ethiopia. Brent learned early from an Ethiopian elder that if he taught a mother, you would be teaching the entire family. That single piece of insight launched his career. There was no reading material in Ethiopia for children. Brent prepared and printed children’s stories. They circulated the printed booklets throughout Ethiopia. That experience led to Brent’s first book The Lion’s Whiskers (co-authored by his good friend Russell Davis and published in 1959).

Brent published seven books with Russell Davis between 1959 and 1963. Beyond 1963, Brent was immersed in his overseas career with the Peace Corps and the Ford Foundation. In 1982, Brent published his first book with Paul Conkin, Morning Star, Black Sun: The Northern Cheyenne Indians and America's Energy Crisis. The last of their many collaborations was published in 1997. From then through 2002, Brent published with his daughter Jennifer, who lived in D.C. This was Brent’s monument series for young readers. Their Vietnam Veterans Memorial was one of his best-selling books ever.

Brent Ashabranner died in 2016. Brent, a U.S. Navy veteran, and his wife Martha are buried in Arlington National Cemetery – the subject of one of Brent’s many books.

Paul Conklin retired and moved to Port Townsend, Washington, an artist’s colony on the Pacific Coast. My wife and I with our middle daughter visited Paul and his wife Ruth Merryman inn Port Townsend. The small town is two ferryboat rides from Seattle.

Paul passed away in 2003. I only found out when his obituary appeared in the New York Times. I was in shock. I immediately called Brent in Williamsburg. Brent was as surprised as I was. We had no idea that Paul was dying of cancer. He was only 74 years old.

There was one other thing that neither Brent nor I knew. As Paul’s obituary in the New York Times explained:

Mr. Conklin’s work appeared in National Geographic, Time magazine, The New York Times and other publications. One of his most striking images, which appeared in Time, was that of a young protestor placing a daisy in the flower of a National Guardman’s rifle during the demonstration at the Pentagon against the Vietnam War.

Paul served in the U.S. Army, where he learned Russian and became enamored with photography. He earned a master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University. In 1959 (pre-Peace Corps), Paul was a staff writer for the Minneapolis Star and Tribune. He was assigned to the team covering Khrushchev’s visit to Iowa. Paul had the byline for the Star on the story of Khrushchev’s famous visit to the farm of Roswell Garst in Coon Rapids, Iowa. Paul never told me about that in all our time together. I only discovered it after his death. Paul always was very positive in his remarks as to the quality of the Minneapolis newspapers.

Brent Ashabranner, Paul Conklin and I shared a deep interest and appreciation for multiculturalism, ethnic inclusivity and cross-culturalism. We traveled throughout the world to that end. That was the common interest which was the basis for our friendship. Subsequently, I connected deeper with Brent on writing and with Paul on photography. Both were older than me, Brent by 29 years and Paul by 21 years. We bonded well on our sense of universal humanity. We understood the importance to young people and to democracy of MORAL EDUCATION. The power of books, whether literature, non-fiction scholarly works or photographic essays, is transformative. Brent and Paul’s books conveyed in words and images the misery, suffering and injustice in our world. The intent was to inspire empathy and perhaps even compassion (active love to alleviate misery, suffering and injustice).

My two current book projects, both nearing completion after decades of work, follow this sense of Brent and Paul. Both weave the transformative power of literature to inspire compassion to make this world a better place for all humanity. One is on the African American movement for emancipation, enfranchisement and equal opportunity and the writings of Frederick Douglass and W.E.B. Du Bois. The other is about the impact of classic Russian literature (Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Chekhov and more) upon a Lithuanian librarian who assisted and, in some few cases, saved Jews during the Nazi occupation.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.